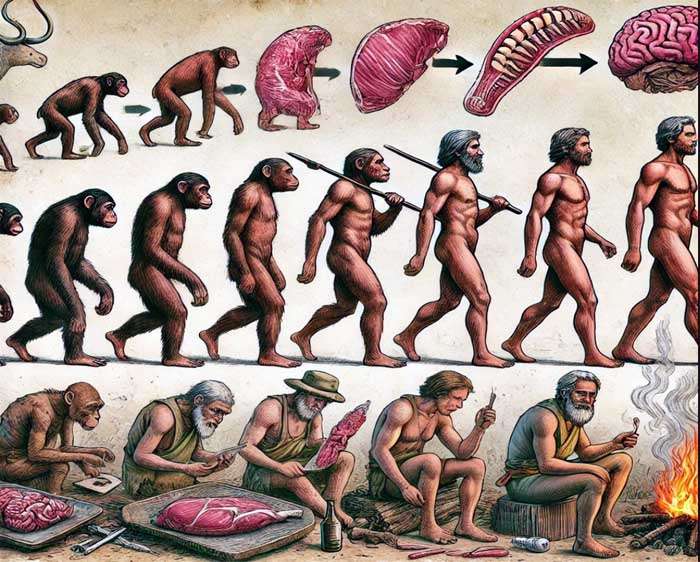

Human evolution is marked by remarkable transformations, but few are as profound as the growth of our brains. How did this happen? A fascinating answer lies in the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis, a ground-breaking theory proposed by Leslie Aiello and Peter Wheeler in 1995. Their work challenges conventional wisdom, asserting that our evolutionary success stems not from simply needing bigger brains but from the revolutionary dietary shift to eating meat. This shift enabled our brains to grow—at the expense of our digestive systems. Let’s explore how this extraordinary transformation unfolded.

The Origins: Kleiber’s Law

The foundation of the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis lies in Kleiber’s Law, named after Swiss physiologist Max Kleiber. In the mid-20th century, Kleiber discovered a consistent relationship between an animal’s body weight and its metabolic rate. Across species, larger animals burn more calories, but not in direct proportion to their size. Kleiber’s graph – a simple, hand-drawn masterpiece – demonstrates this universal correlation. Humans, like all other creatures, fall on this metabolic line.

Aiello and Wheeler used this principle to ask a provocative question: If humans evolved from primates, how did our ancestors maintain the same metabolic constraints while developing larger brains? The answer, they found, involved a trade-off within the body: as our brains grew, another metabolically expensive organ had to shrink. The clear candidate? The gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Brains Over Bowels: The Trade-Off

The human brain is a metabolic powerhouse, consuming about 20% of our resting energy despite accounting for only 2% of our body weight. By comparison, our closest relatives, such as chimpanzees and gorillas, have much smaller brains and larger digestive systems. These differences reflect dietary adaptations. Primates with plant-heavy diets require large guts to break down fibrous vegetation, while carnivorous diets – rich in nutrient-dense meat – require less digestive effort.

Aiello and Wheeler demonstrated that as early humans transitioned to eating meat, their digestive systems could afford to shrink. This freed up energy to support the growth of larger brains. Kleiber’s Law dictated that overall energy expenditure couldn’t increase, so the body had to redistribute resources. The gut’s loss became the brain’s gain.

The Evidence in Our Anatomy

The anatomical changes accompanying this trade-off are striking. Fossil records show that early hominins like Australopithecus afarensis (famously known as “Lucy”) had large bellies, similar to modern great apes. These protruding abdomens reflect the sizeable digestive systems necessary for processing low-quality, plant-based diets. In contrast, Homo sapiens exhibit a narrower waistline, evidence of a reduced gut. This shift aligns with our reliance on a higher-quality diet, particularly meat.

Even today, we see this pattern among hunter-gatherer populations. For example, photographs of Inuit people living traditional lifestyles reveal lean physiques optimized for energy-efficient metabolisms fuelled by meat and fat. Their diets – high in animal protein and low in carbohydrates – highlight the enduring connection between meat consumption and human evolution.

Meat: The Catalyst for Change

Why was meat such a game-changer? Plants, even in large quantities, struggle to provide the calories and nutrients needed to sustain a growing brain. Consider this: to obtain 65% of daily calories from carrots, one would need to eat over 10 pounds daily. Wild plants, smaller and less energy-dense than modern varieties, would require even greater volumes. Meat, on the other hand, offers a compact, nutrient-rich package. Protein, fat, and essential micronutrients like iron and B vitamins made it possible to fuel brain growth without overtaxing the digestive system.

Evidence from archaeological sites supports this timeline. Around 2 million years ago, early humans began hunting large game, a behavior that coincided with a significant increase in cranial capacity. Meat consumption provided the energy needed to sustain these larger brains, reinforcing the feedback loop: better nutrition supported more complex behaviors, which, in turn, enhanced survival and reproduction.

Rethinking Human Evolution

The Expensive Tissue Hypothesis challenges traditional narratives that emphasize the role of foraging complexity in driving brain growth. Aiello and Wheeler argued instead that it was the shift to a meat-based diet that enabled our brains to develop. In essence, we didn’t evolve to eat meat – we evolved because we ate meat.

This perspective reframes human evolution as a process shaped by dietary innovation. The development of tools, mastery of fire, and eventual social cooperation around hunting all stemmed from this foundational change. Meat provided the fuel not just for survival but for the emergence of culture, language, and technology.

The Legacy of the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis

Aiello and Wheeler’s theory has become one of the most cited papers in anthropology, despite initial skepticism. When first submitted to the journal Current Anthropology, reviewers deemed it too complex for readers. Today, it’s celebrated as a transformative idea that reshaped our understanding of human evolution.

As writer Lierre Keith eloquently put it in her book The Vegetarian Myth: “The wild herds of aurochs and horses invented us out of their bodies, their nutrient-dense tissues gestating the human brain.” This poetic reflection captures the essence of the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis: our evolution was not just about survival but about thriving through the gift of meat.

Conclusion

The Expensive Tissue Hypothesis offers profound insights into what makes us human. By shifting to a meat-based diet, our ancestors unlocked the metabolic potential for larger brains, paving the way for innovation and progress. This evolutionary trade-off – sacrificing gut for brain – remains a defining feature of our species. It’s a powerful reminder that our journey as humans has always been shaped by the foods we eat. Far from being mere sustenance, meat was the spark that lit the fire of human ingenuity.